About this deal

From Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Portable Museum’ Boîte-en-valise of the early 1940s to the latest interventions by artists in museums’ displays, merchandise and education, artists of the last seventy years have often turned their attention to the ideas underpinning the museum. Clark’s photographs hint at the emotional connections between curators and collections staff and “their” objects. Curators like show off their storerooms. Seb Chan writes about discovering strange things in museum collections: “That is part of the texture and nuance that museum insiders love — and some of the best museum experiences are those where you chance upon a particularly quirky or strange set of objects.” Museum sense is acquired by working with objects and collections. It’s more than academic knowledge. It’s more than collector’s expertise. It comes from hands-on work with collections: building them, handling them, the long, slow process of making sense of art, history, or nature from them, and of using them to connect with the larger world. In the Storeroom There is something special, and essential, about the curatorial way of knowing. But it can be problematic, too narrowly defined and sharply focused. Remember the Jenks Museum! Curators also need to learn, from audiences and communities, new ways of knowing objects. We need to add to shared authority, the mantra of museum reform over the past decade or two, shared ways of knowing, and new ways of sharing. We need to connect as well as collect. What curators need to do, I argue, is to share their collections, their knowledge, and especially their ways of knowing, with other people — with audiences and with community members. Curators know things. So do other people. Connecting will make both museums and communities stronger.

Fascinating examination of the museum’s unconventional role in contemporary art....Highly recommended.”— Library Journal Anthropology museums have a new understanding of source communities as essential to their work. The National Museum of Natural History’s Recovering Voices program, for example, works with communities from which collections were gathered not just to understand the collections, but also to document and revitalize language and knowledge traditions. This makes collections useful to the museum and also to the communities. One important aspect of this knowledge comes from the curator’s physical connections with the objects. They have the objects, and privileged access to them. Whatever there is to an object that can’t be can’t be described or photographed or digitized — that’s a place to look for particular curatorial knowledge. Geoghegan and Hess offer this list of some of these qualities: “three-dimensionality, weight, texture, surface temperature, smell, taste and spatiotemporal presences.”

Open Library

What can we learn from the materiality of the thing? “Mind in Matter,” Jules Prown’s seminal essay on material culture, calls for “sensory engagement” with the object. The material culture analyst “handles, lifts, uses, walks through, or experiments physically with the object.” What might using the thing tell us? Objects provoke affect; curators respond to them emotionally. Prown calls for “the empathetic linking of the material…world of the object with the perceiver’s world of existence and experience.” Used for planting, eating, decoration, and ceremony, corn and seeds are central to Zuni culture. These samples in the Smithsonian collection may be all that remain of some Zuni heirloom plant varieties. Images: Keren Yairi, Recovering Voices, Smithsonian Institution. Curators of scientific collections, too, exercise their own form of connoisseurship, of object knowledge: Philip S. Doughty, keeper of geology at the Ulster Museum, defined this as “Hunches, intuition…the apparent mystique is in reality a synthesis of a large mass of detail, the product of generations of talented geological curators who have developed, tested and refined skills and practices.” It’s in the storeroom that curators examine objects. Curators know about things. In part, that’s because they know facts about particular things — they’re experts in seventeenth-century pottery, or dinosaurs, or art. But there’s another part to curatorial knowledge: sometimes, it’s not that they know about particular objects, but that they know how to think about objects, or ask questions about objects, that they have a feeling for how objects work in history. They have a general understanding of about material culture or taxonomy or art history, a sense of the big picture, a knowledge of the history of collecting, and a network of other curators to call upon. They also have a certain healthy skepticism, antennae that go up when something’s not quite right.

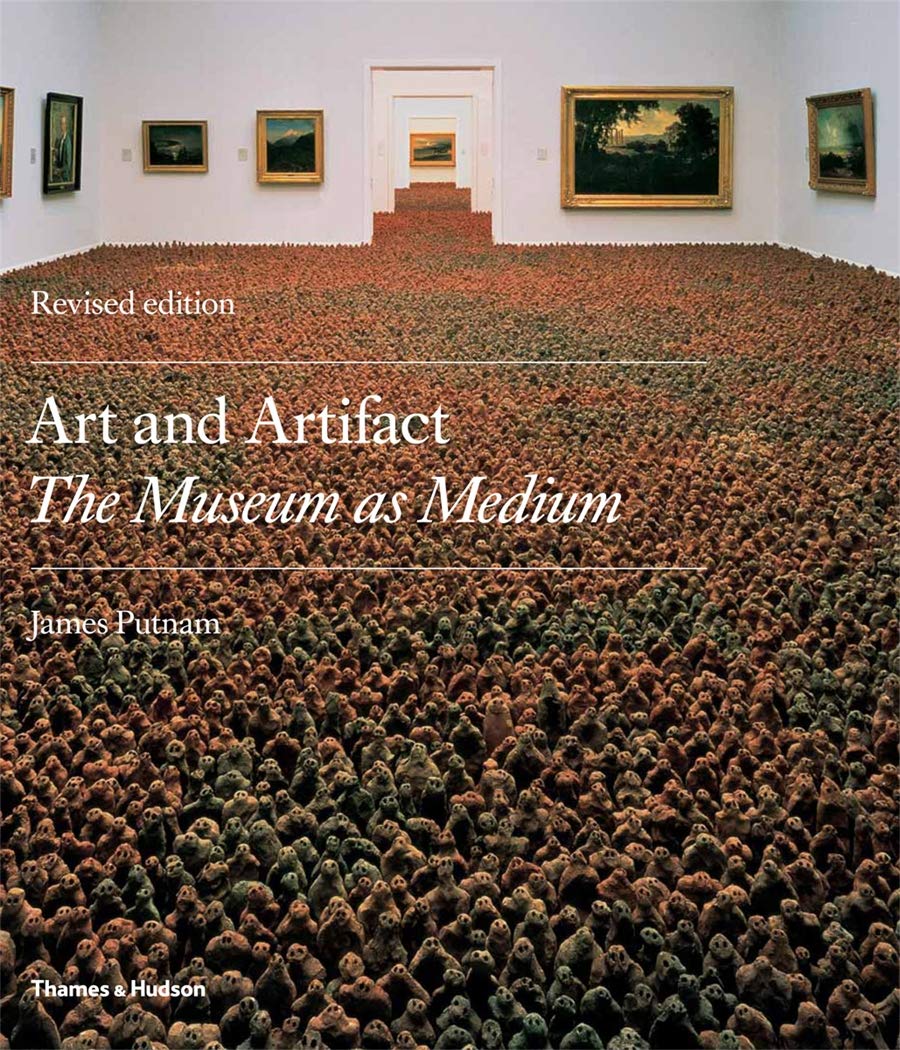

In the beginning museums displayed collections of objects and artifacts, known as a WunderKammer – this consisted of storing objects of a certain category on display in vitrines and cabinets. This traditional way of display has set an example for contemporary art and how we as the visitor are expected to view it; simply by looking with little to no interaction. In the history of traditional display, contemporary artists such as Damien Hirst have adapted their style of work to this method of display. In Hirst’s piece ‘Dead Ends Died Out, Explored 1993’, rows of cigarette butts have been stubbed out in different ways, evenly spaced out in rows in a vitrine. Overall the piece is a neat display that provides a sense of symmetry; it is quite pleasing on the eye to look at despite the objects being a product of waste that you would typically see discarded on a pavement. This book examines one of the most important and intriguing themes in art today: the often obsessive relationship between artist and museum.

This is a vexed — and therefore important — time to be making a case for real artifacts and the skills and knowledge of curators. Museums are once again at a moment of revolution. Their position in the cultural landscape is uncertain. For some, their collections seem irredeemably tainted as colonialist. For others, the world of the digital and virtual seems more interesting than the actual and real. Andrea Witcomb, Australian museum curator and author, asks: “is curatorship a smiling profession?” She takes the term from media studies scholar John Hartley, who defines it as those trades where “performance is measured by consumer satisfaction…where knowledge is niceness and education is entertainment.” He contrasts the smiling professions to those which “continue their disciplinary, classical, clubby and institutionalized maleness, as bastions of older notions of power, enemies of smiling.” We might say: is curatorship people work, not just object work? I believe that curatorship is people work; that it should be a smiling profession. This is not a new idea. George Brown Goode, the first director of the United States National Museum mentioned earlier for his insistence on curators’ special “museum sense,” also insisted that “No man is fitted to be a museum officer who is disposed to repel students or inquirers or to place obstacles in the way of access to the material under his charge.” Frederic Lucas, curator-in-chief of the Brooklyn Museum at the end of the nineteenth century, wrote that curators must “make the knowledge of others available and understandable by the public.” Displaying art and artifacts — making exhibitions — is a skill that depends upon the curator’s intimate knowledge of the objects, their knowledge of context, and their connections to audience. A good exhibition is an argument from art and artifact, designed to communicate with its audience. Conversation

The first half of this essay explained the curatorial skills that allow deep connections between the curator and museums collections. That’s a necessary first step, but not enough. We define curatorial skills too narrowly defined when we limit them to collections. I want to expand the definition curatorial work to include all of the ways that collections might connect — with communities, with audiences, and with each other. Curators need to know how to make connections.

Collections are what make museums unique. Museum collections are more than objects; they are carefully chosen assemblages, the product of a curatorial way of knowing. They are sustained by curatorial expertise. Curators have a distinctive way of understanding objects, making arguments with them, and telling stories with them. Otherwise staid and practical curators slip into poetry when they try to describe this ability to understand objects. George Brown Goode, the first director of the US National Museum, called it “that special endowment… ‘the museum sense.’” Others talk about “object-feel,” or “a good eye.”

Great Deal

Great Deal